When Manoeuvring – Is Knowing How to Handle a Ship All You Need?

I open a glimpse of a particular moment of the manoeuvre:

Let’s secure the tugboat!

Bringing a ship to the quay, or unmooring and accompanying it out of the Port obstructions, means “planning an operation”.

A bit like looking at the entire figure, choosing the puzzle pieces and arranging them properly to ensure they fit together well.

Tying, nocking or securing a tug – the term used varies from Port to Port – is a delicate operation.

We try to understand the correct procedures to avoid unnecessary risks and make the operation smooth and effective.

Over time, numerous accidents have occurred involving tugboats operating near moving ships.

In most cases, we can identify speed as the leading cause of these accidents! Then, we have human error, lack of experience and the type of tugboat used concerning the manoeuvre execution.

In reality, there is another aspect that emerges above all.

I am referring to the natural division of competencies.

To become a pilot, you follow a precise path that matures into specific and in-depth professionalism.

A complete vision is reached only after experiences gained over many years of problem-solving.

Initially, we tend to focus on the “core” of the manoeuvre, the technique and its success, a broad and challenging goal.

It is only when a certain degree of composure arises in carrying out the work that one can consider, with interest and effectiveness, also the outline of the core: the aesthetics of the manoeuvre, the fluidity, the objective balance of decisions and advice and, essential, the role and dynamics of the other subjects more closely involved. I am referring to the ship’s captain with his crew, the mooring men and the tugs’ captains.

It is not enough to know that they are there; you have to be able to look at things from their point of view and understand their problems, their needs and their strengths. Only this way will you be able to work better and more safely.

It is not evident that a pilot knows the characteristics of the tug he will fix at the bow. And it is not sure that he is perfectly aware of the difficulties that the captain of the tug might encounter for that extra knot of the speed of the ship or the possible effects of a tow line released too quickly aft.

As I have already said, this is so important, which rises in the ranking of priorities only after other aspects of the manoeuvre become so familiar that they are no longer considered priority problems.

It takes time.

In this perspective, I want to address, in light and discursive way, the points that need a shared mental passage.

Before we get into it, however, we need to talk briefly about the forces and effects a tugboat is subjected to when it sails near a moving ship.

These forces increase with increasing ship speed and decreasing ship-tug distance: the higher the speed and the shorter the distance, the greater the interaction between the two hulls. In addition to these two factors, the forms of the ship’s hull, the under-keel clearance, the ship’s trim, the draft, etc., also contribute to increasing the effects.

The areas most affected are those close to the bow, much less near the ship’s centre. That is mainly due to the hull’s shape and is particularly insidious when the tug approaches.

Knowing what you’re getting into is virtually impossible at that stage. As already mentioned, the effects undergo numerous influences, and the experience of the tugboat captain, combined with the tug’s manoeuvring characteristics, dramatically affects the general level of safety of the operation, but the sure thing is that:

Decreasing the speed also reduces the effects of interaction.

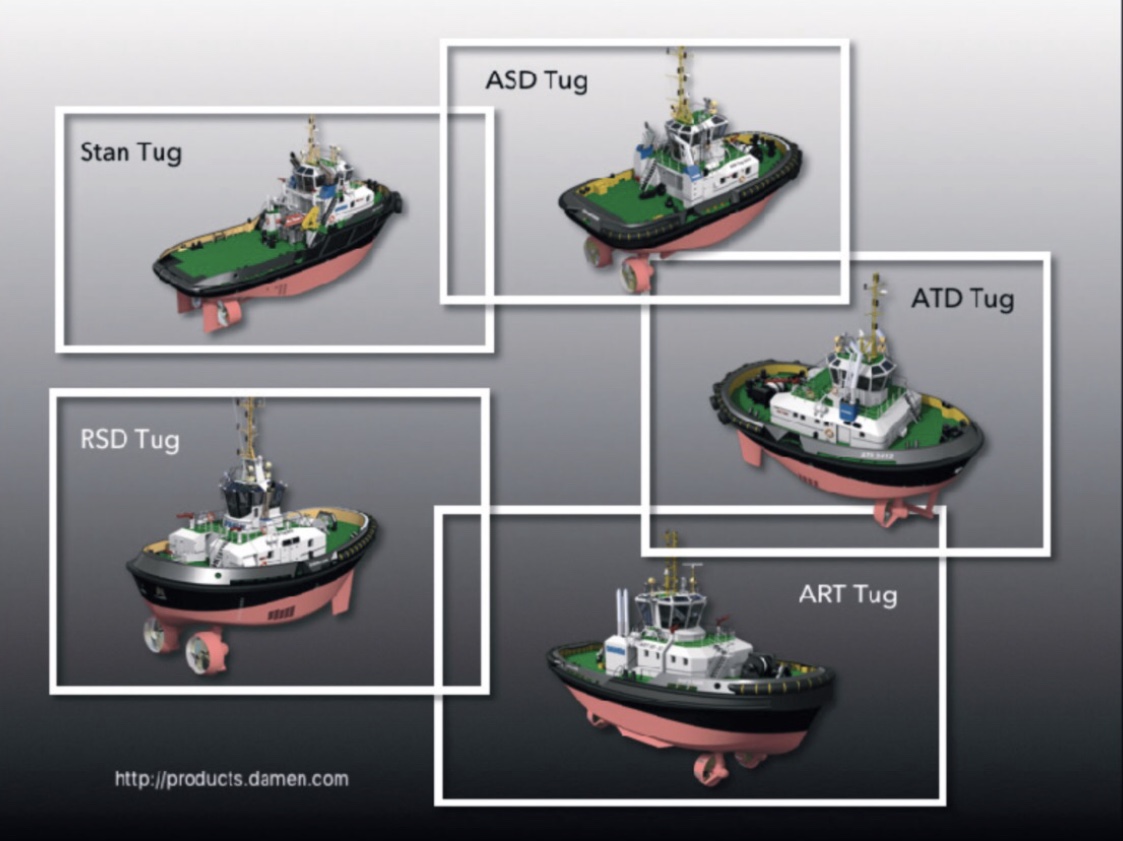

Wanting to postpone the study of a topic that deserves more than a few lines, I simplify by citing only some of the most used tugs in the world: the conventional ones, the azimuth stern drive or ASD and the Tractor Tugs, or ATD, so called because they have the propellers positioned towards the bow.

I have already said that the area most subject to these forces of interaction is the forward one, and the tugboat secured forward is necessarily found to operate very close to the hull. Those who have their thrusters close to the ship’s bulb, in case of need to quickly disengage from a potentially dangerous situation, must use rudders or thrusters in an area subject to unpredictable and non-linear forces. That is why most accidents occur with the tug made fast forward and equipped with stern propulsion.

Given a choice, using the Tractor Tugs forward would be better.

In any case, two rules that pilots should always respect are the following:

- If more tugs are made fast at the bow, always turn the one in the centre first because, in the event of an emergency (blackout, breakdown, etc.), the lateral escape routes would be clear;

- If using more than one tug, turn the one aft first; this way, he can intervene, in case of need, helping control the ship or slowing down its speed while trying to turn the tugboat forward.

Regarding the procedure for approaching the tugboat to the bow of the moving ship, I consider any frontal approach dangerous.

Whether the tugboat waits for the vessel along its route and then anticipates it once it reaches it or – even worse – the tugboat goes towards it in the counter-race. If the engine or the steering gears fail, the impact would probably be inevitable.

The solution I prefer is the one that sees the tug alongside the ship in a parallel course, overtaking it and, remaining lateral to the bow on the leeward side, takes the heaving line and begins the completely free nocking operations.

Let’s talk about speed now—a delicate topic influenced by several variables.

- if we are talking about ASD or a traditional tugboat with stern propulsion to secure forward, the lower the speed, the better it is; I would say that a maximum limit could be 6 knots;

- if we use a Tractor Tug, then pilots should also consider the top speed of the tugboat and the experience of its captain, but I would say that 6/7 knots are still fine (from personal experience and listening to the opinion of several tugboat captains, I would say that also higher speeds are acceptable);

- When the tug has to be secured aft or working sideways, the “safety” problem takes on a different weight and, consequently, speed also has other significance; 6/8 knots can be acceptable.

It is necessary to underline how, for a tugboat captain, experience, personal ability, and knowledge of his unit greatly influence the “safety” factor.

Also, in this case, as in almost all situations, knowing and admitting one’s limits and demonstrating balance and objectivity contributes significantly to the containment of risks and, consequently, accidents.

Let’s now make some considerations on the “ship” side.

It is customary to use the local language when communicating with tugs. That is because the mooring crews and the shore personnel involved in the manoeuvre need to be aware and understand what is happening.

During the exchange of information with the ship’s captain, it is essential to highlight the SWL of the bollard, to which will be secured the tow line. The pilot must share this information with all the actors. The crew must report the various phases of coupling the tugs to the bridge and stay away from the towline once the tugboat pulls. It is also necessary that the pilot inform the captain of the operating modes of the tugboats in the different manoeuvring phases.

When releasing the tow lines, especially the stern one, advise the staff at the manoeuvring station to slack it down slowly to prevent it from ending up in the tugboat’s thrusters.

The pilot must inform the tugboat captain:

- on the SWL of the bollard they will use to secure it;

- the condition/characteristics of the ship (draft, minimum speed, any problems);

- on the berth assigned to the vessel and the manoeuvre execution.

One of the problems that sometimes arise concerns the timing of the players on the field: it is imperative that the tug arrives on time and, if this is not possible, that it warns to allow the pilot adjust the ship’s speed accordingly.

Likewise, the ship’s crew must be ready for the tug’s arrival to avoid dangerous situations.

It is an unnecessary risk for the tugboat to stay under the bow longer than strictly necessary.

Furthermore, when securing the tug, the ship must maintain constant course and speed, and it is, in any case, a good practice to always warn the tug’s captain of any changes.

One thing that the captain of the tugboat, in my opinion, must take into account is that the pilot, very often, is not fully aware of the characteristics of his tug. That means he should have no problem making suggestions if they are functional to work in progress.

As I anticipated at the beginning of the article, what I wrote is nothing more than a “taste” of one of the many delicate phases of the manoeuvre.

In the future, we will touch on other topics underlining the aspect of effectiveness, coordination of the parties, professionalism, management of unexpected events and safety.

Read other articles in the blog section.