How Disconnected is the Anchor from the Propeller and the Rudder?

Over the years the anchor as an aid to maneuvering has given way – in order of importance – to the variable pitch and thrusters.

Not many years ago, it was customary to set up a manoeuvre to flank a quay, with the ship side not favourable to the Paddle-wheel effect, providing for the use of the anchor.

In this regard, I want to report an experience gained during my period as a trainee pilot.

“The pilot who trained me in the manoeuvre had a lot of experience and the courage/patience to let the trainee pilot continue to manage almost to the “point of no return”.

It is a good thing because the adrenaline caused by a “near impact”, a manoeuvre saved as late as possible, leaves an unforgettable experience and is worth more than a book of theory.

We were aboard a one-hundred-meter-long ship with a draft of seven and a half meters, a single prop with a left-handed fixed pitch, traditional rudder and no bow thruster.

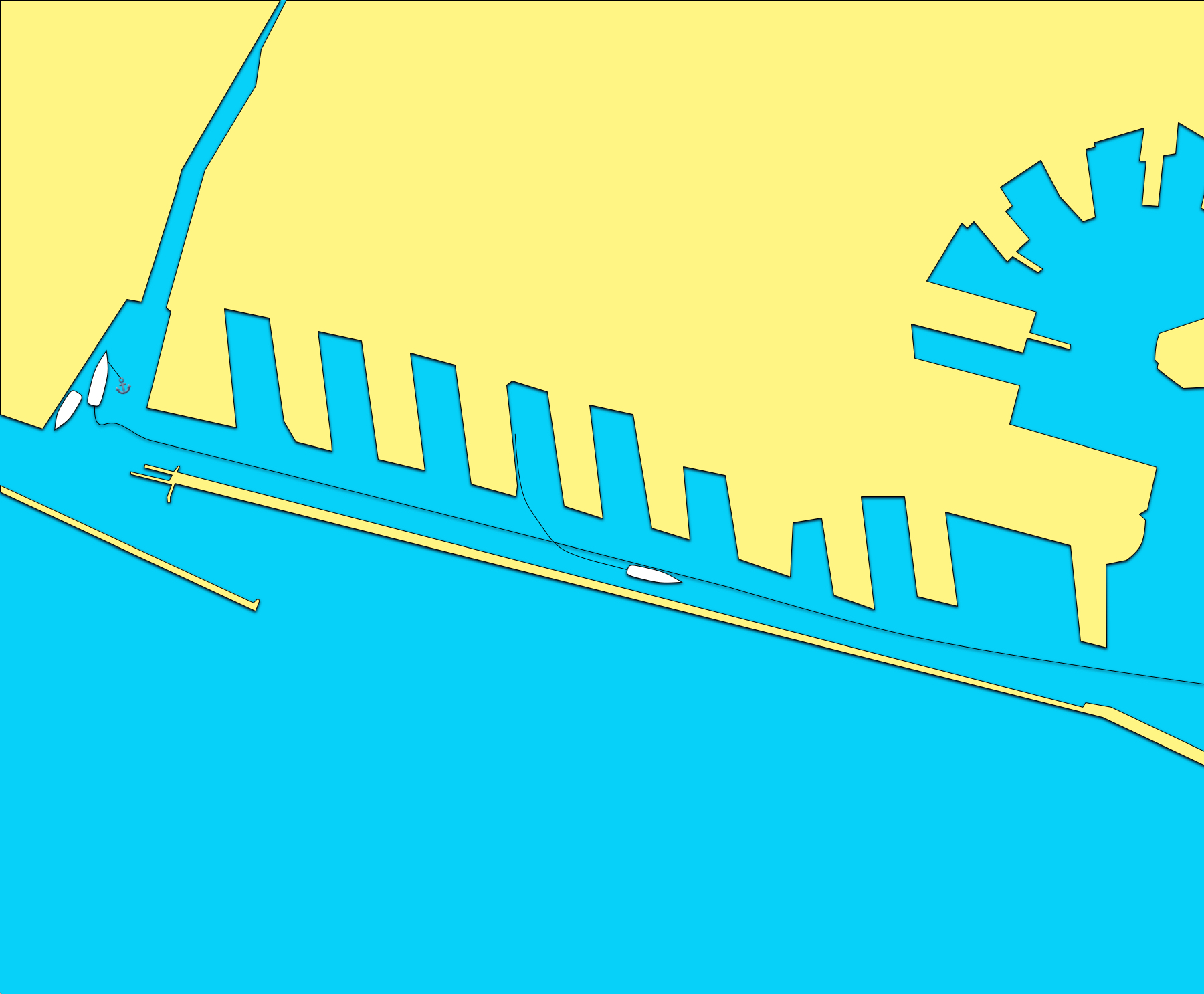

We had to cover about two miles of the canal, turn 90 degrees to starboard, and approach the quay with the port side without turning.

Shortly after entering the canal, another pilot aboard a departing ship asked us to increase the speed to allow him to release the moorings.

My quick reasoning was limited to considering that I was aboard a small ship, which amounted to “small problems” for me.

I took the engine to Half Ahead, and we passed half the canal at seven knots. Once the transit for the other ship was cleared, I reduced to Slow Ahead, but the speed dropped only one knot and, to do so, it took a long time, but inside I was calm because I kept thinking that “the ship was small “…

I went down to Dead Slow Ahead a few hundred meters from the ninety-degree turn point. In short, I realized I had a high speed relative to the current situation, but it was too late.

I stopped the engine, but the loaded ship was too heavy and slow to respond to the command.

I began to sweat cold: I could already see myself against the ship moored before us.

We had to turn, so I started the engine again, but with the Dead Slow, the turning rate was always too slow, and I was forced to increase it to Half Ahead. The rudder began to respond well at the expense of a speed that started to rise again.

The scenario presented to us was the following: a ship moored to the port and our destination a hundred meters ahead, two hundred and fifty meters ahead, everything ended: only concrete.

To close the circle, I can say that we were dealing with a speed close to six knots and the paddle-wheel effect, which, in reverse, would have made us swing the bow toward the quay.

By now, I was in a panic.

The pilot intervened.

He immediately gave the rudder hard to starboard. As soon as the ship began to turn, he put the engine Full Astern, recovering the rudder in the middle: the effect of the propeller interrupted the turning and recalled the bow to port; at that point, he dropped the starboard anchor. He paid out one and a half shackles in the water and then spun another half-length.

Result: After a few minutes, we were moored on the quay, ideally in position.

Considerations:

- The first evident thing is the difference between the trainee pilot’s limit and that of the pilot due to a question of the habit of reacting in critical situations faced in the thousands of manoeuvres already carried out. I add the practice of casual use of the anchor, which eliminates hesitation.

- The theory is the essential basis, but the practice concretizes the words by engraving the experience in the memory.

- Speed is not an absolute value but relative to the contingent situation.

- The size of the ship is also often relative: usually, the manoeuvring aids are proportional to the tonnage, and the draft can make a small vessel very difficult to steer.

- The safety of the manoeuvre in which you are engaged is the most important thing. In this case, making the other pilot wait a few more minutes for unberthing would not have brought any consequences, while increasing the speed created a situation of potential danger.

- The most serious mistake was not to foresee the following steps, arriving at the turning point near the berth without possibly slowing down the speed.

- The proper sequence would have foreseen a progressive reduction in speed to reach the turning point with about two knots and then accelerate in the turning, ensuring greater control. Once turned and the course stabilized, it was necessary to stop the engine, drop the anchor, and dredge it.

In this story several points have been highlighted, among which we find the planning of the use of the anchor.

To make it fluid, using the anchor in case of need would not be the wrong drop it from time to time, even just for training.

Unfortunately, the effectiveness of this tool nowadays is appreciated above all in emergencies. Situations in which the speed of intervention is the factor that, most of the time, determines the control of events or the inevitable impact.

In general, the advantages of its use are numerous:

- control of the bow swing toward the quay;

- stopping the ship with minimal use of the engine;

- management of the course with the dredging anchor;

- positioning of the anchor as an aid for subsequent unmooring;

- and so on.

Controllable pitch and thrusters made things easier.

As we all know, without going into too much detail, fixed-pitch propellers have blades integral to the hub, and it is impossible to act on their orientation. This aspect involves a whole series of limits that we must take into account:

- The engine must be stopped and restarted to reverse the direction of motion with the axis coupled in the reverse order—each time, a new start is needed, which needs air, which is not endless.

- Depending on the rudder of the ship we handle, it will have its minimum steering speed. Some, equipped with a large rudder surface, keep the control at a minimum speed rate, others less. In any case, they all have a limit.

The anchor is the ideal solution to balance the scores in these conditions.

We have said that the advent of controllable pitch propellers and thrusters has changed the situation.

Let’s see why.

First, let’s refresh the memory by defining pitch:

The pitch is the distance theoretically travelled in one complete revolution by the propeller, neglecting the compliance of the fluid, which corresponds to the space it would travel if it moved inside a solid body.

One of the revolutions that occurred in the settings of the maneuvers is due precisely to the possibility of varying the pitch of the propeller at will, a situation that applies, in particular, to medium/small ships. In other words, those where the anchor often replaced the work of any tug boat very well.

Variable-controllable pitch propellers always rotate in the same direction at constant revolutions.

No more starts problems and ease of adjusting the speed according to the need.

This system brings various defects, such as the difficulty in maintaining the course at zero pitch due to the continuous rotation of the axis. The yield in reverse is generally poor and accompanied by a strong propeller effect and several others we will not address in this context.

The fact is that the possibility of acting on the pace to adjust the speed allows for greater control over the manoeuvre; if we add a bow thruster, then the anchor truly becomes a thing that, in these conditions, can be done without.

But the anchor, despite the frequency of its use, has decreased considerably in recent years and remains one of the most important cards to play.

It has happened to me only about fifteen times, in more than twenty years as a pilot, that I have had to use them in emergencies. Still, I assure you that if I had not been “familiar” with using this aid on those occasions, the financial damage that would have ensued would have been extremely high.

For those who have not yet done so, I recommend you also look at the article “Anchors: those at the bow are not earrings!”