Damn “Coanda Effect”!

I have to tell the truth: before experiencing it in reality, I didn’t know it! I’m not even sure I studied it at school. It is also true that many physical laws or theorems that I learned at Nautical if only without a brief review, I cannot expose on the spot. Still, I don’t remember ever studying the Coanda effect! Yet such a singular name, I should remember.

Instead, I have experienced it!

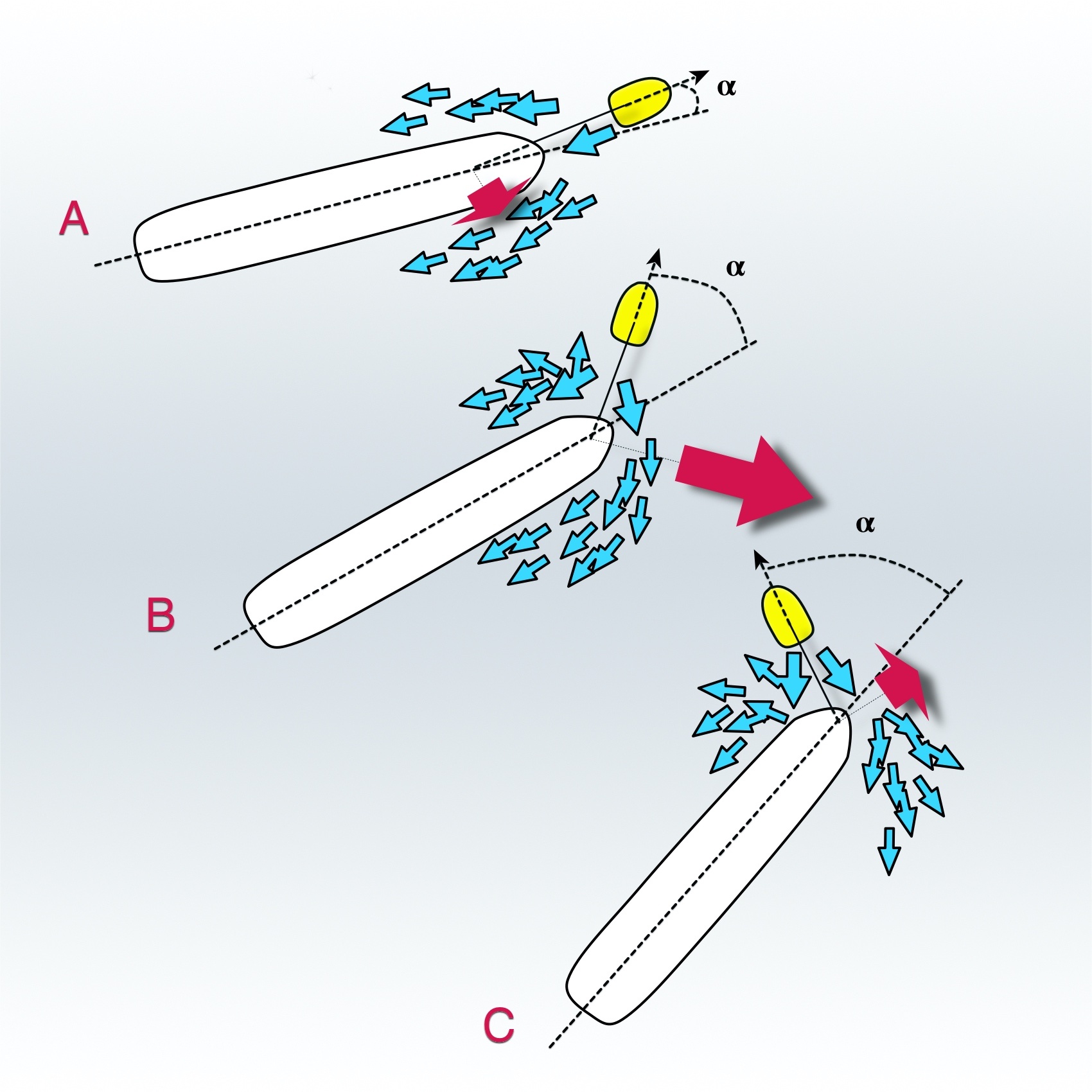

To handle ships in the canal, it is necessary: first of all, to study the theory of hydrodynamic effects; it is then essential to experience its existence in daily practice; finally, if the ‘effects’ were insidious for that type of manoeuvre, we must implement specific measures such as – if the available manoeuvring space permits – the lengthening of the tow cable by enough to make the wake effect against the ship’s hull irrelevant. (as shown in the following illustration).

The most common effects – described in many ships handling texts – are due to the interactions between vessels and seabed, ships/ships, ships and docks; we speak of attractions and rejections.

Bank Suction and Bank Cushion. They are determined by different positive or negative pressures acting on the ship’s hull.

Positive pressures repel, and negative ones attract.

Also, in our book “A Bordo Con Il Pilota” (soon to be translated into English), we address the subject with detailed explanations and practical examples because they are part of every Captain’s baggage.

I guess someone reading will smile.

Pilot work is essentially practical work.

In the pouring of experience during the apprenticeship year, the student pilot is instructed and filled with knowledge by his future colleagues. The training continues beyond in the following years. Each manoeuvre teaches something, and it is common to believe that “it takes at least five years to make a pilot”.

Memories...

When I was a training pilot, it was common to moor ships 150 meters long by 25 meters wide, moving backwards in a channel only 50 meters wide.

Passing from pilot to pilot, I compared everyone's precautions and "tricks" and, based on them, forged my style. There is not an infinite range of different techniques; the same manoeuvre is usually done in a couple of ways, maybe three. However, the nuances are innumerable.

In that particularly delicate circumstance, some pilots used both tugs to maintain the correct attitude of the ship. In contrast, others gave the only initial order to the stern "tractor" to keep the centre of the channel, using only the forward tug to correct any yaws.

The latter obtained a more straightforward and less "worked" manoeuvre.

What happened to the former was that when they moved the towing tug from the canal axis to correct a deviation, Its wake was wedged between the ship and the bank, creating a pressure zone that countered the action of the towline.

The engine and rudder often had to be used repeatedly to help the tugboat in its task.

Is this the Coanda effect? Not exactly.

More appropriately, we can blame the pressure generated between shore structures and the ship and the repulsion that comes from it. However, if we notice the same phenomenon by removing the channel and positioning our ship in larger spaces, well, yes, then we are experiencing the Coanda effect!

Like Bernoulli and Venturi, Henry Coanda is well known; those who have studied flying understand who and what we are talking about. The theory describes the Coanda effect through the speed variation of a flow that strikes a convex surface: “the part in close contact with the shell slows down due to friction, the outer part accelerates and a pressure reduction is generated, but since the fluid is molecularly cohesive, it remains adherent to the convex surface following its profile, developing, at the same time, a low-pressure zone “.

Low pressure = attraction.

Thus, under certain conditions and at a certain pulling angle, the tugboat wake can hit the ship’s side, and part of its flow creates a force of attraction on the opposite side. This force can cancel or even reverse the direction of rotation that we want to give to the ship.

If now finished reading these few lines, we leave the page and search for the “Coanda effect” on Google, we can find enormous amounts of information. Among these, the example of the spoon under the tap is pleasant and instructive.

I did it! I took the spoon, opened the tap and, holding it with two fingers so that it was free to swing, made the water flow on the convex surface, empirically experiencing the attraction the fluid exerts on it.

After this experiment, the above becomes more understandable and difficult to forget.

At the next opportunity, observe the ship’s behaviour and, among the effects you will experience, try to recognise the one described in this article. With a little attention and refining our manoeuvring technique, you will see that it will become easy to prevent and compensate.